African sovereignty and influence in an increasingly interconnected world

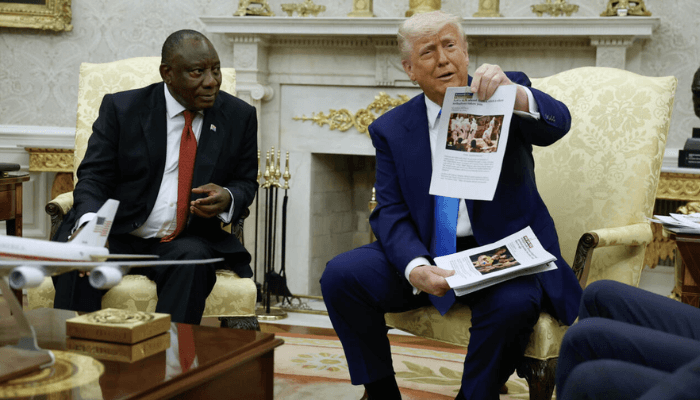

On 21 May 2025, U.S. President Donald Trump met South African President Cyril Ramaphosa in the Oval Office. The discussion took an unexpected turn when Trump cited unverified claims of systematic attacks on white farmers in South Africa, allegations that Ramaphosa and his government have consistently and firmly denied.

“Pan-Africanism has long focused on achieving full sovereignty, specifically freedom from colonial structures and external control.”

While the exchange may seem a bilateral skirmish, it revealed something far broader: the contested terrain between national sovereignty and global influence, particularly for countries navigating both domestic priorities and foreign pressure. In South Africa’s case, land reform remains a sensitive internal issue, yet it is repeatedly drawn into international discourse, often shaped by actors with limited understanding or skewed agendas.

The deeper question this raises is not simply about sovereignty but about what sovereignty means in today’s world and who truly exercises it.

This dilemma is not unique to African states. Under Trump, the United States itself has exposed the fragility of sovereignty even within Western democracies. Europe, for instance, remains reliant on the U.S. security umbrella through NATO, a dependence largely unchanged since World War II. Can Germany, France, or the UK claim strategic autonomy if their defence is underwritten by American power?

Economic sovereignty is similarly compromised. Trump’s tariffs and regulatory threats have repeatedly forced U.S. allies and rivals alike to recalibrate policy. Informational sovereignty is eroded by reliance on U.S.-based tech platforms like Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Apple, not only in Africa but across Europe and Asia. Even the U.S., despite being the global system’s primary architect, is constrained by multilateral agreements, legal regimes, and economic interdependence.

For African thinkers, especially within the Pan-Africanist tradition, these contradictions merit reflection. Pan-Africanism has long focused on achieving full sovereignty, specifically freedom from colonial structures and external control. But in a global order where even superpowers lack full autonomy, perhaps the more relevant goal is not absolute sovereignty but increased influence.

Read also: Breaking the chains of IMF dependence: A path toward economic sovereignty for African nations

Legally, all states are sovereign. But in practice, global influence, defined by a country’s ability to shape international norms, rules, and agendas, has become the more decisive metric of power. Sovereignty without influence leaves countries vulnerable to decisions made elsewhere. Africa is not without leverage. Its cultural capital is immense and underutilised. Afrobeats, Kwaito, Highlife, and other genres dominate streaming charts globally. Artists such as Burna Boy, Angelique Kidjo, and Youssou N’Dour command large, transnational audiences. These cultural assets represent a powerful form of soft power, one that could be strategically mobilised to build global affinity, drive economic opportunity, and enhance diplomatic presence.

Beyond culture, Africa’s natural resources remain indispensable to the global economy. The continent holds an estimated 30 percent of the world’s mineral reserves, including cobalt, lithium, and coltan, critical to electric vehicles, smartphones, and clean energy technologies. Platinum, gold, and rare earth elements are equally central to both luxury markets and industrial production. Without African resources, the green transition stalls.

Environmental relevance is another pillar of Africa’s potential influence. The Congo Basin, the world’s second-largest rainforest, plays a critical role in global carbon absorption. Africa’s ecosystems are essential to biodiversity, food security, and climate stability. Engaging Africa as a climate stakeholder is not optional; it is a global necessity.

Then there is Africa’s demographic trajectory. With over 70 percent of its population under the age of 30 and projections that one in four people globally will be African by 2050, the continent is emerging as both a workforce and consumer market of strategic significance, especially as Europe, Japan, and China contend with ageing populations.

Yet turning indispensability into true influence requires strategic coordination. Africa must move from being a supplier of raw assets to a co-author of global systems. This means controlling value chains, investing in innovation, and, most critically, negotiating as a bloc. Fragmentation dilutes leverage. Unity amplifies it.

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is a crucial step toward this vision, as is a more assertive role for the African Union. A continental approach to climate diplomacy, trade negotiations, and technological governance would allow Africa to speak with one voice, transforming its position from reactive to agenda-setting.

The recent Trump–Ramaphosa meeting should not be interpreted solely through the lens of South Africa–U.S. relations. It is emblematic of a broader need for African states to define a collective diplomatic posture in a world where influence, not isolation, confers protection.

Sovereignty remains a cornerstone of international law. But in today’s interdependent world, the power to shape rules and steer global agendas is the truer measure of autonomy. Africa’s path forward lies not in withdrawing from global structures but in mastering them on its own terms.